Sheffield's Investment Zone: an opportunity to showcase the city’s “green” future?

Celebrating Sheffield’s pioneering approach to urban landscapes

Lower Don Valley Landscape Framework

Project date: 1991-1995

Team:

Rob Pearson, Sheffield Development Corporation - the start of a life-long partnership…

Dr Oliver Gilbert, University of Sheffield - in memory of a collaboration that was full of wonder and joy.

The UK’s first Investment Zone has been declared spanning Sheffield city centre, the Lower Don Valley, Rotherham and beyond. The economic objectives are clear, but there is little mention of sustainability.

This feels like a major omission and a lost opportunity. The Investment Zone is home to many businesses that support a sustainable future. Sheffield has committed to net zero carbon by 2030 and is known for its pioneering work to create sustainable urban places. Why not build on this experience and know-how to create the UK’s “greenest” Investment Zone?

30 years ago, as part of Sheffield Development Corporation, we explored how the landscape of an industrial area in the 20th century could tell the story of a man-made place with a focus on nature conservation, urban ecology, history and identity.

In the last 20 years in Sheffield the thinking has moved on dramatically: the Green Estate, the University of Sheffield and Sheffield City Council have collaborated to research, test and pioneer sustainable approaches to urban landscape that both address the climate and biodiversity emergencies and create beautiful and distinctive places.

Together they have developed a world-class set of products and practices that are changing the face of Sheffield city centre, the parks and open spaces of its urban neighbourhoods and the roadsides in Rotherham, whilst supporting local skills, jobs and enterprise. This is a place-based and community-centred approach that could and should become a hallmark of the new Investment Zone.

This post describes the thinking behind the work we did 30 years ago in the Lower Don Valley to create an authentic urban environment based on ecological principles - what worked and what didn’t - and what you would do differently today, knowing what we know now.

Imagine extending Grey to Green across Sheffield city centre and using the river, canal, railway, roads and development sites of the Lower Don Valley to showcase what an adaptive and resilient urban environment should be.

What we did 30 years ago

I was employed by Sheffield Development Corporation in the early 1990s to develop a landscape framework for the industrial valley that would attract new investment, working with Rob Pearson who led on the development plans and projects for the valley.

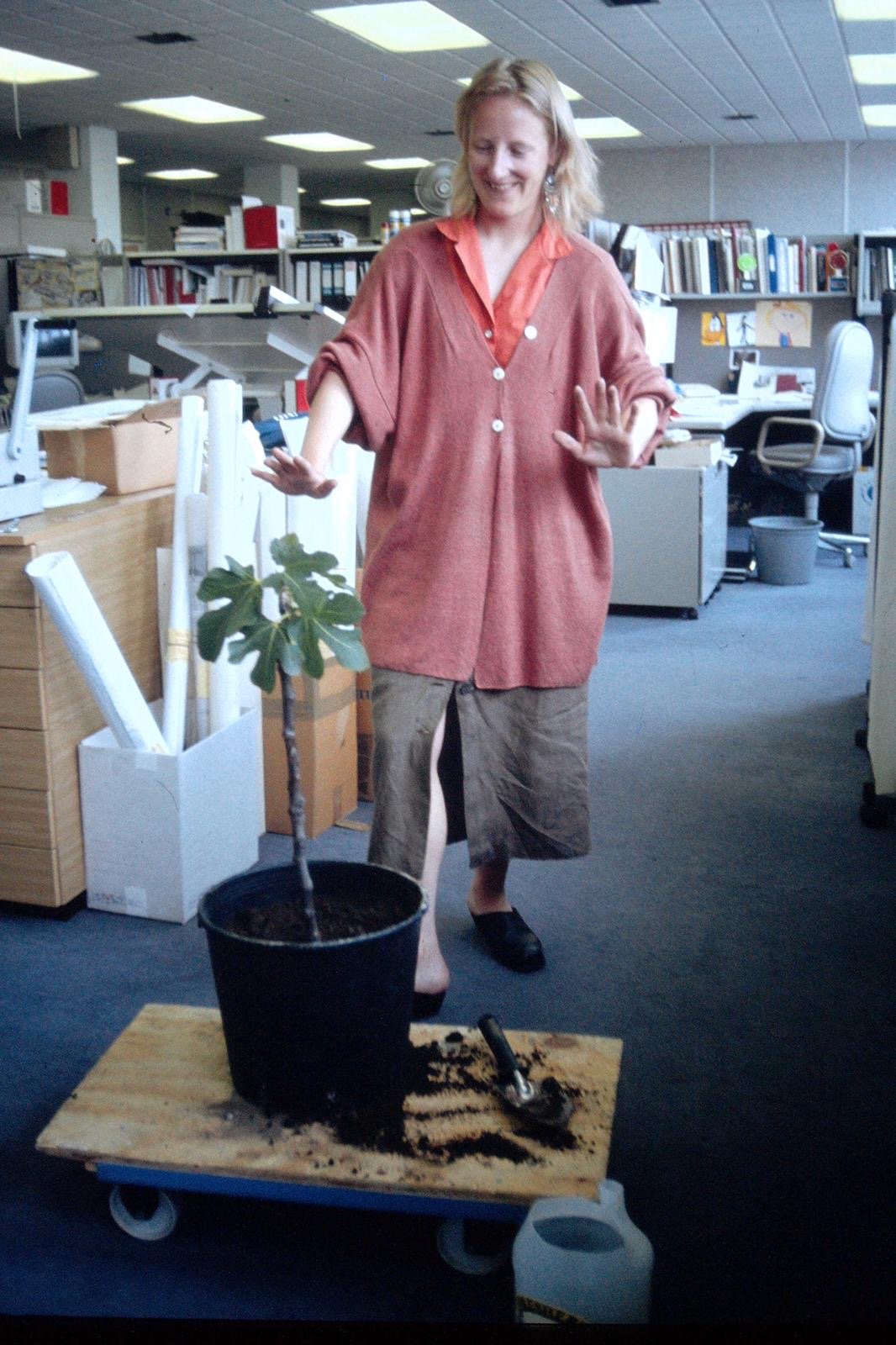

landscape manager at sheffield development corporation, (outfit WEIRDLY on brand)

rob pearson, development manager at sheffield development corporation

.

the don valley in the early 1990s - large tracts of land available for redevelopment

The area retained a decent level of steel production but needed much less workspace and fewer people to do so. The result was large tracts of derelict land that were to be re-packaged for new uses.

The challenge was to create a new image and setting whilst not losing sight of the history of the place that had generated a global brand - Made in Sheffield.

a valley of industry

The plan was to protect and enhance the natural and heritage features of the valley; and to use these to develop a design language for the urban landscape that would communicate the story of Sheffield’s industry. We wanted to create a place that was distinctively “Sheffield”, rather than an “any place” business park.

Our approach was to:

#1 Uncover the natural features and human impacts that had shaped the history of the place.

#2 Explore the stories of the people who lived and worked there.

#3 Communicate those features and stories through a new landscape framework, both natural and man-made.

Discovering the Lower Don Valley

Jessop’s warehouse, one of the buildings demolished in the 1990s

I got to know the Lower Don Valley through the eyes of Andrew Whitham, my first friend in Sheffield. In 1986, before Meadowhall was built, he introduced me to the glamour of Tinsley viaduct at night, the black sheds of Forgemasters, the derelict buildings and wastelands. We wandered through the ruins of the steelworks, exploring old warehouses and plundering, amongst other things, an old light fitting that still hangs in my house.

When it came to thinking about a landscape framework for the valley, I was particularly inspired by the work of Dr Oliver Gilbert who exposed the relationship between the ecology of the valley and its history as the centre of Sheffield's steelmaking: the home of cutlery, tools, springs, fencing, aero engine parts, pipes, oil rig components, armour plating, medical instruments, rolled steel strip and Torvill and Dean's skate blades.

dr oliver gilbert “lichenologist and wildlife hunter in the jungle of Sheffield”

Through Oliver, described in his obituary as "lichenologist and wildlife hunter in the jungle of Sheffield", I discovered a different and no less intriguing side to the valley.

Oliver taught in the landscape design department at the University of Sheffield for over 30 years, which is where I met him when I was student there. He was an inspirational and engaging tutor, with an almost child-like interest in ideas, backed up by forensic knowledge and research.

We stayed in touch after I graduated and I invited him to collaborate on developing a landscape identity for the Lower Don Valley, and later for the Dearne Valley.

He was interested in plant communities that were not conventionally seen as valuable, especially urban habitats. For example, he discovered that the plants that grow under Japanese knotweed, that bane of contemporary Britain, were almost identical to those that grow under our revered ancient woodland.

He taught us as landscape architects to look closely at the plants and natural features of a place to design places that would be locally distinctive and that would "work" ie plant mixes that would thrive without intensive maintenance.

The landscape framework

the urban grain of the valley, tight near the city centre and large scale near the motorway

The overall concept for the Lower Don Valley development framework was to create distinct areas within the valley that reflected the move from the tight 19th century urban grain of cutlery workshops near the city centre to the gigantic rolling mills of the big steel producers and the sprawl of Meadowhall near the M1.

The idea for the landscape framework was that the valleyside to the north and the four corridors along the valley floor - the river, rail, canal and new main road - would link the different development areas to provide coherence and a sense of place.

Sheffield Development Corporation took a broad view of environmental issues and supported a range of work including air and water quality; reclamation of contaminated land; refurbishment of existing buildings & structures; landscape structure and nature conservation; and the South Yorkshire Forest.

Background work on the flora and fauna had been carried out in previous years by Sheffield City Council supported by dedicated local experts and interest groups including the Five Weirs Walk Trust, Sorby Natural History Society and Sheffield Wildlife Trust. Work on the built heritage had also been undertaken. The aim was to integrate the existing wildlife, habitat capital and heritage of the valley into the permanent landscape structure to create a place that reflected its distinctive features and cultural history.

The valley sides and the four corridors along the valley floor link the different development zones

We developed a plan to accentuate the valley form by planting woodlands on the steep slopes to the north that rise up to Wincobank ridge and by creating a different design language for each of the four corridors that run the length of the valley floor: the river Don, the Tinsley canal, the railway and a new road that linked the new development sites.

Wincobank has an ancient hill fort, so we chose native woodland as the planting there and on the lower slopes.

But on the valley floor, we tuned into the urban habitats that were a product of its more recent history, developing planting mixes based on the spontaneous vegetation that had developed naturally over time - habitats that ranged from wetland to meadow, scrub and woodland - and hard landscape features characteristic of the valley.

We wanted to create a distinctive and urban place by giving emphasis to plant communities and built elements that are typical of cities, as opposed to imitating ones that occur in the countryside.

The wooded valleyside

Wincobank ancient hillfort with its historic oak woodland inspired our planting for the valley ridges.

The well-defined topography of the river valley has created a range of habitat conditions closely related to land form. Although much of the original soil and vegetation has gone, remnants of the pre-industrial landscape still exist on sites that are hard to develop, for example oak woodland and acid grassland on the steep slopes of Wincobank Ridge.

We added to the natural oak/birch/rowan woodland through extensive new planting on the ridges either side of the valley, an early contribution to the South Yorkshire Forest. Alongside, acid grasslands, including patches of heather, gorse and broom, were established. 30 years on, this woodland is clearly visible from the valley floor.

The hill fort is a popular walking spot. In the 2000s I commissioned, with regeneration funding, an arts project called Journeys to Hidden Places from a team called Y SO?, led by Gordon Young. Two of the eleven sculptures are at Wincobank Hill: Posh Pillar and her Daughters mark the entrance to the hill and include poems by a local schoolgirl, Ebenezer Elliott and Mary Anne Rawson, a Wincobank resident and anti-slavery campaigner . The Star-crossed Queen at Jenkin Road celebrates Cartimandua, the queen of the Brigantes who inhabited the area during the first century CE.

The belt of mixed deciduous woodland that formerly occupied the middle and lower valley slopes has been largely lost through development over the centuries. On sites where it was possible to recreate woodland we introduced an ash/hawthorn mix, supported by cherry, white beam and small-leaved lime to reference what had been there originally.

woodland on wincobank hill overlooking the don valley

the star-crossed queen at jenkin road, wincobank photo courtesy of friends of wincobank hill

posh pillar and her daughters at the entrance to wincobank hill thanks to www.picturesheffield.com

The River Don, Sheffield’s fig forest and the Ecology Park

a fig forest. our sheffield one is not quite as impressive but you get the general idea. image with thanks from an Article for the Canals and Rivers Trust by David Bramwell

The Don Valley provided the wooded slopes, waterpower and flat land for the cutlery and steel industries to thrive. The river was the driving force behind the development of the industrial valley and remains its most powerful natural feature, rich in wildlife and distinctive ecology. The landscape plan aimed to give the river much greater prominence, access and visibility.

One by-product of the collapse in the steel industry was that the water quality improved and wildlife started to return to the Don. We helped conserve the best sites and funded a small study to track populations of kingfisher and water vole.

cuttings of wild figs from the river don were used to extend the fig forest

Through funding extensions to the Five Weirs Walk, the riverside route that links the city centre to Meadowhall, we were able to open up this valuable place for more people to enjoy, and to create walking and cycling routes that now go as far as Rotherham. The route included a new nature reserve at Salmon Pastures and took in a fascinating network of weirs, mill races and ponds that had powered the cutlery industry and which are nodes of habitat diversity.

We also created an Ecology Park as an environmental education resource for the city on an island of land with the river on one side, Sanderson’s Mill race on another and railway on the other two sides.

New development sites fronted onto the river and opened up views to it. We strengthened the riverine woodland.

On the flood plain past industrialisation has removed all but the woodland along the river which is characterised by mature crack willow and, unusually, wild figs.

Oliver wasn't the person who discovered Sheffield's wild figs, but he did work out why they were there in such quantities as Ian Rotherham, Professor of Environmental Geography at Sheffield Hallam University, explains here.

The fig forest, unique in Britain, was a product of river water that was both used for sewage and for tempering steel furnaces, creating the conditions for the seeds of this Mediterranean plant to germinate. It is a great example of how the ‘natural’ landscape can tell the story of the valley’s cultural history. In 1991, Ian Rotherham was part of a group that campaigned to protect the fig forest, the first time this had been achieved for a non-native species, and a small victory for local distinctiveness.

We added crack willow and figs (stems rooted from local plants) along the river itself. On land near the river we added to existing goat and grey willow, elder and orchard apple, alder and ash.

one of the five weirs on the lower don

the sanderson’s mill race ecology park

The figs are not the only urban species connected with the steel industry.

At the Ecology Park soapwort meadows flourished on steel slag alongside birch scrubland, mosses and Pixie-cup lichen. Other lichens grew on concrete blocks previously used to support a Derrick crane.

The Mill Race, now largely disused, had become an important haven for moorhens, mallards, coots, kingfishers, dragonflies and a range of aquatic plants. Fragments of marsh vegetation are the last remaining relics of the marshy meadow of the floodplain from the pre-industrial period. Plants grow here that grow nowhere else in Sheffield, such as sedges and skullcaps.

Here we commissioned the artist David Nash to create one of his growing pieces, Eye of the Needle and Sweeping Birches: birch trees were planted on the river bank at an angle as if parting to reveal a huge oak needle charred by David in a local steelworks.

The sculpture represents the changing nature of Sheffield as it moves away from its heavy industrial past to a more environmentally friendly future. It can be viewed from a steel disc found on the Ecology Park and now relocated to the other side of the river.

Sadly the piece has become overgrown and is scarcely visible. And I understand the Ecology Park has recently been converted to a scrap yard.

Although the river continues to improve in quality, a number of local groups are working to restore it to its natural state - from surviving to thriving. The River Don Project is exploring the feasibility of winning legal rights for the Don in what would be a UK first.

david nash, internationally-renowned sculptor, with eye of the needle and sweeping birches, seen from the viewing platform on the five weirs walk

soapwort meadows flourish on steel slag

eye of the needle and sweeping birches, a david nash growing piece

Annie Proulx wrote about David Nash’s work in the Guardian ahead of a major exhibition at Yorkshire Sculpture Park in 2010:

“He uses chainsaw, axe and fire, gouge and graver to make sculpture where the improbable convinces with delicious wit. In his hands wood seems fabric, as malleable as gold, black as Indian hair, a carbuncled lump. Trees are sliced and inclined, chunks needled, paginated, riddled, elbowed, pierced, incised, long bolts frittered and hollowed, geometrics waffled.”

The Tinsley canal

the canal towpath near tinsley locks

Improvements to Tinsley Locks and major works at Victoria Quays opened up the canal for recreation. Investment in the canal towpath and connections to the Five Weirs Walk helped create a round walk.

Traditional, and where possible reclaimed, canal materials were used for the paths, paving and fencing.

The vegetation of the canal corridor is characterised by open scrub and grassland.

Where woodland had already been created, the intention was to convert it to over time to vegetation dominated by alder, birch, ash, thorn and sallow.

Elsewhere areas of open grassland were retained and planting at Tinsley Locks was tailored to accommodate existing areas of sand sedge.

The railway

railway bridges painted in the livery colours of the former railway companies

Railways criss-cross the valley. The bridges were painted in the livery colours of the former railway companies and viaduct arches refurbished.

The railway corridor contains a number of distinct habitats linked to its use. Our planting mixes took their cue from the species that had naturalised along different sections.

Sidings are traditionally underlain by railway cinders. This provides an acid substrate which supports birch and broom, as well as plants such as Colutea aroboresecens, or bladder Senna, which were becoming associated with railways.

Embankments provide a more alkaline environment. They become colonised by thorn and elder and also support goat and grey willows, orchard apples, ash and buddleia. Cotoneaster salicifolia was also becoming established as a railway species.

Cuttings in Sheffield are normally into coal measures which weather to produce an acid substrate that supports Deschampsia grassland, birch and broom. Thorn, elder and bramble occur where there is tipping from the top.

The new road

Along the new road corridor, we referenced the built history of the valley.

signs made of stainless steel letters

Boundary walls in brick, chunky stone copings, black fencing and a curved black lighting column, reflected the brickwork and massive black sheds of the steelworks.

The names of the development sites echoed the original steelworks or other landmarks - Atlas North, Newhall and Carbrook - there was no attempt to "rebrand" or whitewash what had gone before.

Signs were made of stainless steel letters. Metal artworks and artefacts celebrated the steel industry.

A "new" tree was chosen for the formal avenue planting, a range of Acers, including a red maple, selected for their seasonal interest, formality, because valley bottom is their natural habitat - and because the Chairman of the Development Corporation liked maples!

along the main road boundaries reference the history of the valley: brick, steel and stone

formal avenues of maple along the main road soon after planting

Development sites

brick walls, steel fencing, reclaimed setts and maples at the entrance to a development site

The development sites, located along the new road, referenced specific aspects of the past.

For example, on the development sites around Carbrook Hall, a building that dates from the 17th century, we planted pleached limes and trees that had been introduced to England before 1700, including tulip tree and almond.

To learn how to create the pleaching I spent a delightful morning with the head gardener at Chatsworth, a 17th century house in Derbyshire with a somewhat different history and profile.

The pleaching around the Police building, having been immaculately maintained by Santander for many years, has recently been abandoned. Instead of keeping the stems clear (to create the "hedge on legs" effect), the branches have been allowed to grow creating a solid hedge. The Police who now occupy and manage the site apparently feel that a hedge is more secure.

It is ironic that the only other site I know of in Sheffield (apart from M&S on Ecclesall Road) that has pleached limes is the Police headquarters at Nunnery Square, off the Parkway. Nunnery Square was developed by Andrew Sebire, who also developed Carbrook and who loved the pleaching so much he wanted to recreate it at his next site. I didn't want to point out that there was nothing of the 17th century at Nunnery Square….Unfortunately the Police have massacred the pleaching here too.

pleached limes at carbrook starting to become established

pleached limes at Chatsworth were the inspiration for the planting at carbrook

pleached limes at carbrook soon after planting 30 years ago

the original 17th century panelling in carbrook hall image with thanks to www.picturesheffield.com

stainless steel fencing on a development site on the main road

On other development sites that lined the new road, we referenced the 19th and 20th century fabric of the valley with black metal street furniture, site specific designs of stainless steel or black metal fencing and more formal planting: avenues of maple, ornamental versions of the shrubs on the other corridors and geometric blocks of evergreen, herbaceous and in some places ivy (big mistake).

Some of these plantings have since grown out, some have become hedges and others have been transformed by manufacturers into abstract topiary. (Topiary in unusual places is a bit of a theme in Sheffield.).

Using existing semi-natural plant communities as a model for new landscapes made sense: the plants are well-adapted to the location and should thrive. Unfortunately they thrived somewhat too much, especially as we planted at high densities!

On secondary sites we used off the peg fencing, made in the valley by Tinsley Wire, and simpler planting.

densely planted shrub beds under maples

brick, stone and black metal railings on the main road

tinsley wire’s metal fencing, made in the valley, on secondary roads

Land in store

On land that was awaiting development, we experimented with temporary meadows of wallflower, white clover, snapdragon and lupin sown directly onto brick rubble or subsoil.

They didn’t work, but were a precursor to the city's "pictorial" meadows, later used on housing demolition sites and roadsides in the city and now turned into a world leading Sheffield brand by Professor Nigel Dunnett and the Green Estate.

Temporary meadows were sown onto brick rubble

temporary meadows starting to appear on land in store

sowing a meadow on a site awaiting development

What to do today, knowing what we know now

#1 Grey to Green - Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS)

The biggest omission by far in our plan was the use of Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SuDS). The Grey to Green scheme in Sheffield City Centre is a fantastic example of what SuDS can achieve.

The genius of the Grey to Green scheme is that not only does it promote bio-diversity and create beautiful landscapes, it also manages rainwater run-off from the roads in a way that cleans it from pollutants and reduces flooding.

If you look closely you will see that the Grey to Green roads all drain directly into the planting beds. Specialist “soils” and planting are designed to filter and break down pollutants before slowly releasing clean water into the river. Given that over 25% of micro plastics in the oceans come from run-off from roads, this is an important intervention.

Further extensions to Grey to Green are planned in the city centre. Could it also extend to the Lower Don Valley?

Citu is a housing developer, local to Yorkshire, with a strong commitment to sustainability, as evidenced at their successful sites in Kelham and the Leeds Climate Innovation district. Their development in Attercliffe, where up to 1000 new homes are planned, would be a brilliant opportunity to bring Grey to Green beyond the city centre and into the valley.

grey to green in sheffield photo nigel dunnett

#2 The ‘Sheffield School’ of planting design and Pictorial Meadows

In the last 20 years Professors Nigel Dunnett and Jamie Hitchmough with colleagues at the University of Sheffield have developed, based on experimental research and practical application, an ecological approach to planting of public spaces that has come to be known as the ‘Sheffield School’ of planting design.

The approach integrates ecology and horticulture to achieve low-input and high-impact landscapes that are dynamic, diverse and tuned to nature. Grey to Green is an excellent example, but most of this work has happened outside Sheffield. Let’s see more of it in the city!

One aspect is the use of meadows, both annual and perennial. The mixes that Nigel has developed in partnership with Green Estate, and now sold under the Pictorial Meadows brand, are a million miles away from our attempts 30 years ago. Seen by a global audience at the 2012 London Olympics, and also locally on Rotherham’s main roads and across Manor, close to the Green Estate’s base, these are stunning displays that flower over many months, are rich in bio-diversity and simple to maintain.

This school of planting design, developed in Sheffield, has moved from the primarily decorative solutions that we planted on the main road and development sites of the valley 30 years ago, to designs that also address climate change and bio-diversity.

Using this style of planting on the main roads and development sites of the Investment Zone would send a powerful message about the city’s commitment to sustainability, as well as creating a beautiful street scene.

sheffield school of planting design on a development site at the university of sheffield campus photo nigel dunnett

roadside meadows in rotherham photo pictorial meadows

#3 Local delivery partners for green corridors

30 years ago we tapped into expertise in the University and a range of active groups in the city.

20 years on, there is an established network of delivery partners in the city with the skills and resources to design, plant and maintain sustainable urban landscapes.

The Green Estate, the University of Sheffield, Sheffield City Council and Zac Tudor and colleagues at Arup have the knowledge and track record to create the adaptive and resilient places we need. Most of their work, however, takes place outside the city.

The Investment Zone is an opportunity to change that. And in the process to support local skills, jobs and business.

Medellin in Colombia has created Green Corridors along its main roads and waterways to cool built up areas and clean the air along busy roads whilst increasing biodiversity and making the city more beautiful. As well as direct benefits on climate and quality of life, the project has trained 75 local people to become city gardeners and planting technicians, with the help of staff at the botanical gardens.

There are plenty of other examples of inspirational green corridors in cities. The National Trust has created an urban park on the Castlefield viaduct in Manchester. In Paris the Promenade Plantee was developed 30 years ago (around the time I was working in the Lower Don Valley!) which in turn was the inspiration for New York City’s High Line.

Why not combine green corridors in the Investment Zone with active travel? Sounds like the perfect opportunity for some of the 1.4 million trees pledged by the South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority and a great opportunity to showcase commitment to improving health and wellbeing as well as the environment.

And how about a training/visitor centre at the Green Estate, at its base in the Manor that overlooks the industrial valley?

green estate has the skills to design, plant and maintain urban landscapes like grey to green and the capability to train others from their base in sheffield photo green estate

#4 Legal rights for the River Don?

The River Don Project is exploring the feasibility of winning legal rights for the River Don. What’s the point?

A new rights of nature movement is testing out the impact of giving legal status to non-human actors on our planet, including rivers. This would allow legal representation on behalf of, for example, the River Don to challenge commercial or policy proposals that could have a negative impact on the waterway.

Lots of places around the world have achieved this. But this would be a first for the UK.

Although the quality of the Don has improved significantly since the decline of the steel and related industries from the 1980s, nonetheless water pollution, including sewage spills, is limiting further improvement.

This could be an opportunity for Sheffield to lead the way on tackling the national water quality scandal and our relationship with the planet.

the river don

photo prue chiles

Photo Prue chiles

#5 Showcase for businesses that support sustainability

Some of the activity in the Lower Don Valley that is supporting sustainability is highly visible: active travel routes along the river and canal; Supertram; the Energy Recovery Facility.

But much of it goes on behind closed doors in the scrap yards and metal works of the material recycling industry that is an essential part of the valley’s manufacturing eco-system.

No doubt across the Investment Zone there are multiple examples of cutting-edge work that will provide some of the solutions to the challenges of a net zero carbon future. And we expect to see further growth in this area, for example, the supply chain for retrofitting South Yorkshire’s 600,000 homes. Could this be a setting for investment in specialist environmental technology?

30 years ago, we didn’t shine a light on this work. It would be great to make it visible this time round.

Explore more

Find out more about Grey to Green and Professor Nigel Dunnett’s work - and go and visit the results in Sheffield City Centre.

Visit the Green Estate at the Manor to see their wonderful pictorial meadows.

Read about Medellin’s Green Corridors project here.

Find out more about the National Trust’s Castlefield viaduct park here and read about the Promenade Plantee here.

Find out more about the project to win legal rights for the River Don in this article from Now Then.

This book is a good insight into the work of Oliver Gilbert - The Ecology of Urban Habitats, 1989, O L Gilbert